This paper ‘Slovenia monitors and evaluates the LEADER/CLLD delivery’ by Dr Irma Potočnik Slavič offers an analysis of the processes that have had a key impact on rural development in Slovenia after independence in 1991. It is important for professionals dealing with rural development and, at the same time, contributes to the development of the scientific study of the implementation and effects of rural development policy. It represents the interaction of experts and practitioners in the field of rural development: it connects the university with research institutes, development agencies, development policy makers, decision-makers and direct expert associates who implement rural development policy in the ‘field’.

Slovenia monitors and evaluates the LEADER/CLLD delivery

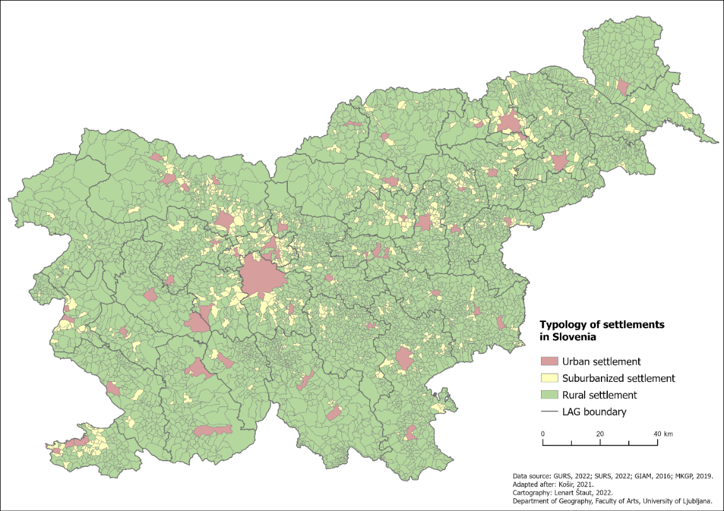

Slovenia has a strong rural character. Slovenia (20,273 km2, 2.1 million inhabitants) has a strong rural character: at NUTS 3 level all regions are defined as rural (7 out of twelve as predominantly rural regions). For the purpose of this research process we followed some of the starting points and findings of previous research (Kovačič et al., 2000; Kladnik and Ravbar, 2004; Nared et al., 2019; Košir, 2021). Therefore, several criteria were used (population density, population change 2020/2012, share of agricultural population in municipality, degree of centrality related to four functions – public administration, education, healthcare, judiciary), and three types of settlements were defined (Fig. 1): rural settlements (5165 or 85.6% of all settlements in Slovenia), suburbanised settlements (816 or 13.5%), and urban settlements (55 or 0.9%).

Fig. 1: Typology of settlements in Slovenia and LAG territories.

Source: Potočnik Slavič et al. 2022, Potočnik Slavič 2024.

Source: Potočnik Slavič et al. 2022, Potočnik Slavič 2024.

The structure of settlements shows that more than four-fifths of all settlements in Slovenia still have a distinct rural character. An operational definition of rural areas is used for the measure LEADER/CLLD: all settlements with less than 10,000 inhabitants count as a rural area (Rural Development Program 2014 ̶ 2020, 2022). Therefore, it is not surprising that this approach covers the entire territory of the country. The later is not the result of a spontaneous development, but of systematic work at all levels in the period before and after the launch of the LEADER approach.

Introducing LEADER in Slovenia. In the implementation of the LEADER/CLLD approach, Slovenia is somehow differing from other Central and Eastern European countries since it already had had experience with a “bottom-up” development approach before joining the EU in 2004. Since 1990s rural areas, rural populations and responsible managing institutions (mostly Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food, MAFF) gained experiences with the implementation of the Integrated Rural Development and Village Renewal projects and the resulting Rural Development Programmes (Cunk Perklič et al. 2020; Cunk Perklič and Jerič 2023). In Slovenia, LEADER/CLLD approach and program have been implemented since 2007. The creation of 33 (2007–2013) and 37 (2014–2020, with smaller changes also in 2021 ̶ 2027) local action groups (LAGs; Fig. 1) has set-up new development structures and new knowledge centres at sub-regional level.

In the early stages of the LEADER approach on the EU level, Slovenia was only a diligent observer, learning from the EU countries that launched the LEADER pilot initiative in 1991. With its accession to the European Union, Slovenia started implementing LEADER, building on its experience, adopting policies and programmes adapted to its own circumstances and setting-up innovative practices (Potočnik Slavič 2024).

Delivery of LEADER/CLLD approach: participatory observation and monitoring placed LAGs in the centre. A mixed group of researchers (from university, institute) and practicians (from LAGs) decided to analyse the implementation and delivery of the LEADER/CLLD approach, therefore it was necessary to obtain a variety of data and information sources and, consequently, to use appropriate methods. A complex research process was set-up, in which an important emphasis was placed on participatory research with actors and stakeholders of the LEADER/CLLD approach actively and equally involved from the scratch.

In several years of work, the authors used a very effective combination of methods, namely:

- quantitative: collection and analysis of primary databases (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food, Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy, Agency of the Republic of Slovenia for Agricultural Markets and Rural Development), implementation of three e-surveys (among LAG members, project implementers, selected local action groups), analysis of newspaper articles, analysis of all LEADER/CLLD projects implemented from 2007 to 2020,

- quantitative-qualitative (analysis of interviews using the Atlas.ti method) and

- qualitative (interviews, focus groups, round table and discussion, reflective thinking, continuous e-correspondence and feedback with LEADER/CLLD actors and stakeholders).

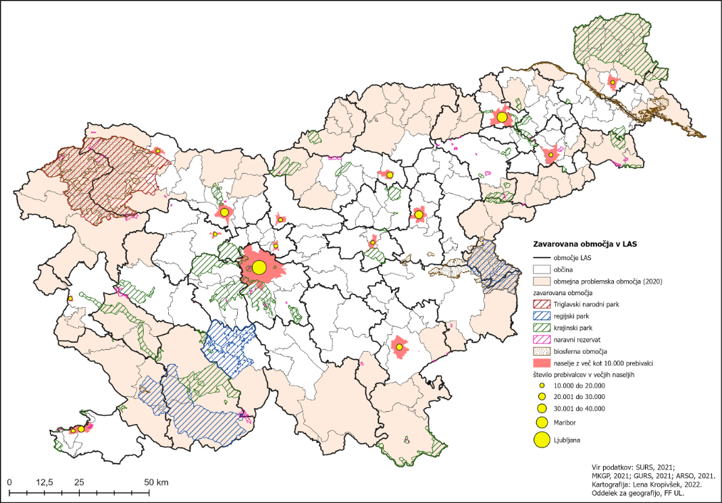

The backbone structure of our research was grounded on three steps (definition of the LAG territory, setting-up structures, implementation of projects; Ray, 2006), and seven LEADER principles. We wanted to prepare a practical handbook which would offer “edible” text, visualization (maps, infographics) and data on LAG level (on demography, economy, partnerships, financial issues, changes in LAG territories, etc.). Herewith, from contextual perspective we focused on: rural development in practice, structured overview of LEADER/CLLD in Slovenia, case studies on LEADER/CLLD delivery (11 LAGs), and the importance of joint learning with and for LEADER/CLLD.

Fig. 2: Several relevant data were calculated and presented on LAG level (for example: the spatial distribution and structure of protected areas).

Source: Potočnik Slavič et al. 2022.

Source: Potočnik Slavič et al. 2022.

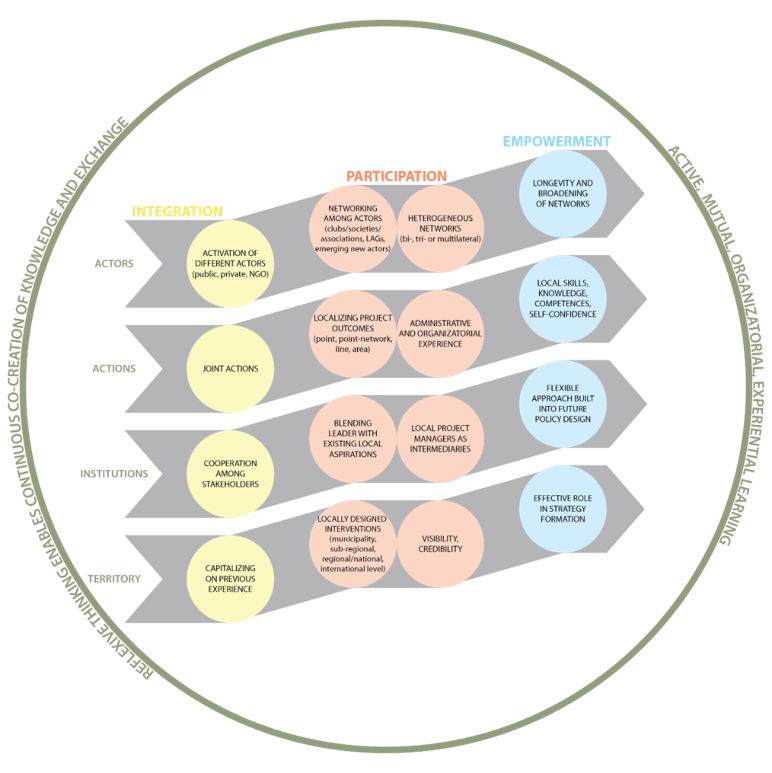

Reflexive thinking on LEADER/CLLD delivery. Slovenian rural areas have been facing different obstacles related to LEADER/CLLD delivery (passivity of the local population and poor response to local initiatives, long-lasting administrative procedures, multi-fund trap, effects of so called ´projectification´, spatially confined impacts with modest visibility on national level, emphasised focus on social and economic development and a clear lack of projects dealing with environmental protection and biodiversity conservation, etc.; Potočnik Slavič et al. 2022, 228-230) which are also relevant in other EU countries (Bosworth et al. 2015; Gkartzios and Lowe 2019; Granberg and Andersson 2015; Konečný 2019; Pollermann 2017; Ray 2006; Servillo 2019; TELI2 2018, etc.). The actual and real differences in the success of the implementation of local development strategies and the achievement of development objectives should not be a reason to doubt the performance of individual LAGs, but a trigger for even more effective animation and promotion of local development, coupled with simultaneous systemic support from the national level (Potočnik Slavič et al., 2022).

A primary step in the process of rural policy co-creation is creating spaces in which people can be ’empowered’ to engage in a process through which they can identify, confront and reflect their problems and solutions (Cornwall and Jewkes1995, 1669). The contribution of the neo-endogenous praxis (such as delivery of LEADER/CLLD) and reflexive thinking about rural development is in understanding how things work on the ground, to rationalise what actually happens in the locality, a way of thinking about how things work in practice, accepting that knowledge about rural development is produced by different actors (Gkartzios and Lowe, 2019).

Fig. 3: Framing the contribution of neo-endogenous reflexive thinking (LEADER practices) to empowerment of rural region.

Source: Potočnik Slavič et al. 2022; Potočnik Slavič 2022.

Source: Potočnik Slavič et al. 2022; Potočnik Slavič 2022.

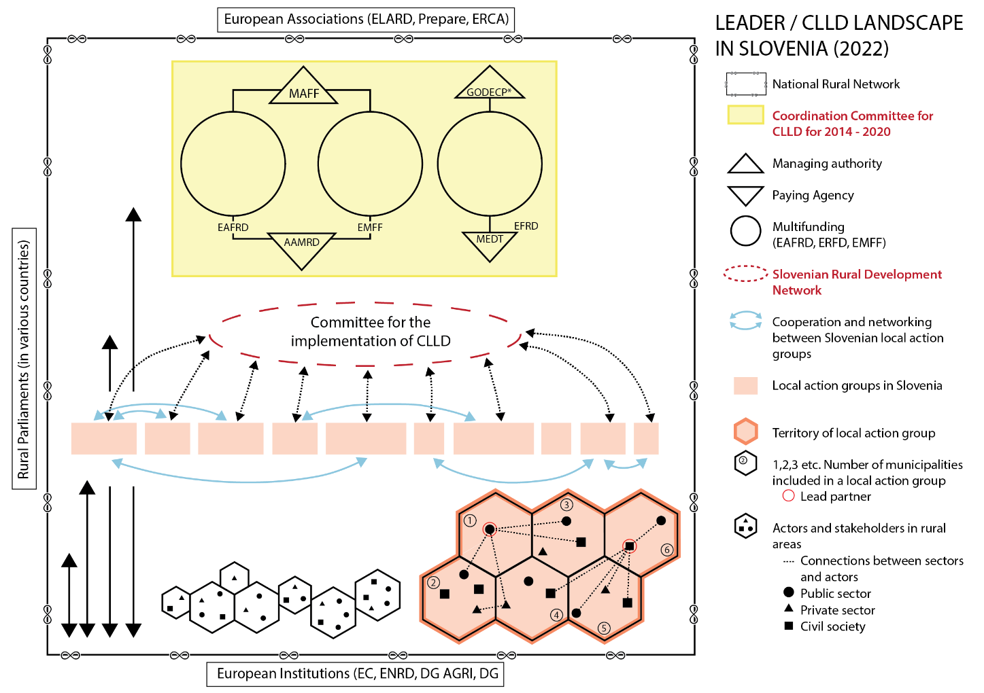

The day-to-day implementation of the LEADER/CLLD approach is mainly the responsibility of local action group employees, who have had a longer time to get to grips with the complex procedures. The implementation of the LEADER/CLLD programme thus brings new skills and experience to rural areas and creates stable jobs. The integration of the three European funds (EAFRD, ERDF, EMFF) also requires increased staff commitment on the part of the Managing Authorities (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food manages the EAFRD and the EMFF; the Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy manages the ERDF; the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology is the intermediate body for the ERDF) and the Agency of the Republic of Slovenia for Agricultural Markets and Rural Development as the paying agency for the EAFRD and the EMFF. The complexity of the procedures in terms of content and time, the in-depth knowledge of the sectoral legislation and the need for coordination at national, regional and local level dictate the need for increased staffing.

Two innovations within the Slovenian LEADER/CLLD landscape. The fact that LEADER/CLLD program delivery is a mixed bottom-up and top-down approach asks for more active and effective cooperation and coordination among indicated levels. Within the LEADER/CLLD landscape in Slovenia (Fig. 4) one is able to observe the bottom-up approach in defining LAG territories and setting-up LAG strucutres (presented in the lower part of Fig. 4). Additionally, one can identify the notions of so-called operational interface. Long (1984; quoted in Wellbrock et al. 2013) defined interfaces as critical sites in which face-to-face encounters occur between individuals or groups representing different interests, resources and power. They are nodes in which the goals, perceptions, interests and character of people may be reshaped as a result of their interaction. Interfaces can thus be defined as nodes in which support for joint learning and innovation is operationalized and people learn to work together (Wellbrock et al. 2013). Operational interfaces are those that are actually working and visible. Within the LEADER/CLLD landscape in Slovenia two operational interfaces might be identified (indicated in red; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: The LEADER/CLLD landscape in Slovenia with indication of two operational interfaces acting as innovations.

Source: Potočnik Slavič et al. 2022, Potočnik Slavič 2024.

Source: Potočnik Slavič et al. 2022, Potočnik Slavič 2024.

The first, the Slovenian Rural Development Network (in Slovene: Društvo za razvoj slovenskega podeželja) is an NGO association which plays a special role in the implementation of the LEADER/CLLD approach and programme in Slovenia. It acts as an operational interface that includes almost all LAGs, several public institutions and individuals. Within this network a special working body (Commission for the Implementation of LEADER/CLLD) was set-up. Over the years, through its activities and cooperation with the managing authorities, it has become recognised as a representative of LAGs´ interests and rural residents. The association has become an important stakeholder and interlocutor in the co-design of development policies at the national level. Through its representatives, it is actively involved at the international level in three areas: in the programming and management of the LEADER/CLLD approach, in the implementation of transnational projects, as well as in learning and participation in international events. The association should continue to actively seek a wider social visibility and a greater role in decision-making related to rural development in Slovenia. This type of operational interface is an important link between different levels of decision-makers in the field of rural development policy, and above all a good network broker, as it takes care of advocating interests, transferring experience from the field, etc.

The second interface is an important Slovenian innovation in LEADER/CLLD delivery, i. e. the Coordination Committee for LEADER/CLLD (in Slovene: Koordinacijski odbor za LEADER/CLLD za 2014 ̶ 2020), which operated in the period 2014 ̶ 2020 and also in period 2021 ̶ 20207. It is an operational interface that connected 3 funds, 2 ministries, 4 different bodies, 5 locations, that is, the managing authorities (MAs) with the paying agency, which was focused on the harmonization of complex rules of the individual European funds involved in CLLD, operations, better coordination with Slovenian Rural Development Network and LAGs, but above all on cross-sector coordination with MAs. Working together and building collective agency is, however, easier said than done. It needs to be learned, developed and institutionalised, requiring institutional learning over a long period of time, with repetitive interactions and trust (Wellbrock et al., 2013). Building collective agency requires joint reflexivity, defined as the ability of a group of people to continuously reflect, monitor and act upon their actions and activities to access their outcomes and adapt their actions accordingly.

References:

Potočnik Slavič, I., Cunder, T., Šabec Korbar, E., Bedrač, M., & Šoster, G. (2022). Izvajanje pristopa LEADER/CLLD v Sloveniji. GeograFF 26. University of Ljubljana Press.

Potočnik Slavič, I. (2024). Co-creation practices address hurdles in LEADER/CLLD delivery – insights from Slovenia. In: Grabski-Kieron, U. (Ed.). Rural geographies in transition: rethinking sustainable futures of rural areas. Ländliche Räume, Vol. 11, 185-199. Berlin.

Potočnik Slavič, I. (2022). The contribution of LEADER to the empowerment of rural areas: the case of the Brkini Region, Slovenia. European Countryside, 14 -1, 1-26, https://sciendo.com/article/10.2478/euco-2022-0001.

Prepared by: Irma Potočnik Slavič, Dr., Senior Lecurer in Rural Geography, Department of Geography (Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia); irma.potocnik@ff.uni-lj.si

Acknowledgements:

The author of this paper would like to express sincere thanks to all local actions groups, various rural actors and stakeholders, as well as co-authors of the scientific monograph on the implementation of LEADER/CLLD in Slovenia (Cunder, T., Šabec Korbar, E., Bedrač, M., Šoster, G.) for their dedicated contribution to discussion and valuable expertise.

For more info you might dive into a scientific monograph on LEADER/CLLD delivery in Slovenia with extended English summary and encompassed rich cartographic representations and infographics. Link: https://doi.org/10.4312/9789612970031

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.